Masculinity, melodrama, and the Black Lodge.

David Lynch: The Unified Field, curated by Robert Cozzolino and on view this past winter at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, showcased approximately ninety works, mostly paintings and drawings, ranging from the filmmaker’s student days at PAFA to the present. As the first major museum exhibition of Lynch’s work, it gives us an incredible opportunity to consider the breadth of the artist’s contribution to a variety of art historical discourses.

Filmmaker and multimedia artist Coleen Fitzgibbon and critic William J. Simmons visited The Unified Field to discuss issues of medium specificity, historical influence, gender, violence, and artistic responsibility. The conversation left them with more questions than answers—a sign, to be sure, of a provocative exhibition.

Will Simmons: Coleen, you’re a multimedia artist in a similar vein as Lynch. Do the various media you use inform one another, or are they all separate, as Lynch suggests?

Coleen Fitzgibbon: I agree with Lynch that still and moving images often arise separately in the mind. A still image might free float, isolated from a traumatic emotion, or because there are no relational values to other images. Images sequenced together, as in movies, can cause an experience similar to a dream state. Some single images create the appearance of a narrative. Here, I’m thinking of Diane Arbus’s photos, such as Eddie Carmel: The Jewish Giant Taken at Home with His Parents, in the Bronx, NY, 1970 or Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, 1962.

WS The Arbus connection must be key. There’s the giant in Twin Peaks, and of course many reformulations of scale in this PAFA show, like Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House (2009).

CF I forgot all about the Twin Peaks giant. I bet Lynch looks at more art than he admits. And his cryptic statement from the press preview—“I still see [film] as a moving painting really”—is a funny thought if we flip it and think of paintings as movie stills. Akira Kurosawa used to raise money for his upcoming films by selling paintings and prints from his newest storyboard. Lynch has said his art is not, in any way, referential to his movies, though there are a few early drawings that clearly relate: Drawing for Eraserhead (1965–68) and Untitled(1970), then Man Throwing Up (1968), which seems very much like his early film Six Men Getting Sick. But putting that aside, don’t you think Lynch is the first experimental filmmaker to bring dream consciousness to the big screen, to the broad public?

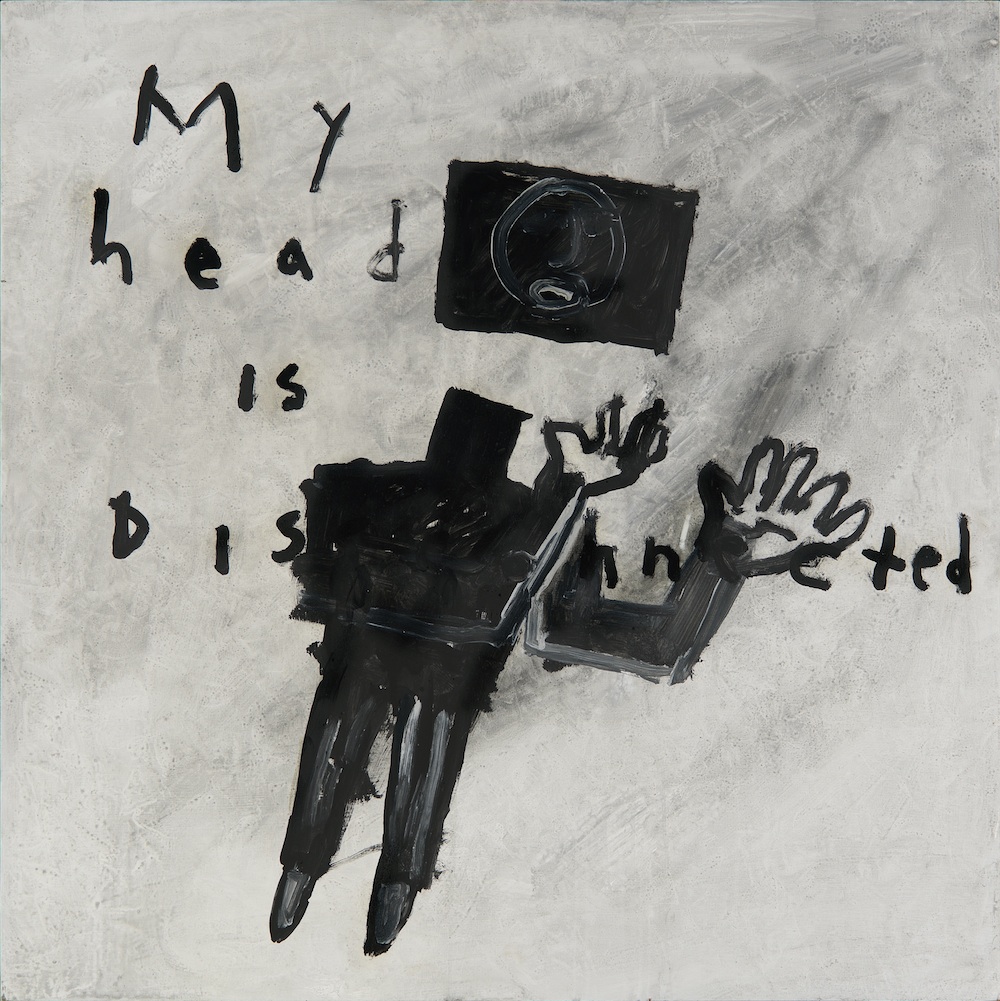

WS Absolutely. I think The Shining might be the next closest thing. But here, it’s especially interesting to see that dream consciousness worked out in very different media. There’s something even more surreal, or hyperreal, in his paintings, it seems, because of the way he integrates text. I kept thinking of Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, especially Lynch’s piece of a body with a camera head, My Head is Disconnected (ca.1994–96). Words and images have no need to exist in seamless collaboration for him, as such a connection might seem important to a narrative filmmaker. He does some kind of damage to the image with words, and vice versa. He seems to be pointing to the violent, erotic nature of the way we produce language and image. This brings me to my next question. I’m really intrigued by the role of gender and sexuality in Lynch’s work. His film and television work, I’ve always thought, is expressly critical of normative gender roles. Dennis Hopper’s character in Blue Velvet, for instance, is kind of a psycho queer! But, things seem much more stable and reified in his paintings, which I don’t think is a result of the medium but rather a different method of handling gender that comes across as less subversive. What do you think?

CF Do you mean Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) in Blue Velvet is equivalent to Norman Bates (Tony Perkins) in Psycho, or that it’s an identification question—as in Lynch’s early film The Grandmother, where the central character is a very young boy whose parents are monstrous? The father figure looks huge and dangerous, growling and hitting the boy, while the mother emits anxious squeaking sounds, and acts in an overtly sexual manner toward her son. The boy, armored in a black tuxedo and bow tie, seems to have sprung to life as a small adult, a male Athena. This young Lynch clone also shows up in Fire Walk With Me too.

WS There seems to be an element of both gender play (remember when Hopper paints Kyle McLaughlin’s face with lipstick) and sexual insecurity. Like Norman Bates, there is a wounded male sexuality that borders on queer, but that connection is tenuous because of the deeply normative and heterosexual roots of those readings of Psycho. It’s funny—I actually usedPsycho as some kind of ridiculous metaphor when I came out to my mother. Needless to say, it didn’t go over well!

CF One wonders about Lynch’s relationship to his parents. Definitely, his images of damaged male sexuality are his most interesting. I also found that smearing of lipstick completely disconcerting. And there is another blood-lipstick-smear scene in Twin Peaks with a crazed crying girl by a mirror. Lynch’s film images of sexual violence toward women, for me, call to mind Perry Smith in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, whose sexuality runs dangerous and subterranean, possibly homosexual without being able to embrace it. Lynch’s women seem to exist largely as objects for attracting male aggression, though Fire Walk With Me seems to attempt a deeper understanding of his female character. I think he has a gender sensibility that is definitely “boy causing trouble,” or male danger, as in his drawings Boy Lights Fire, (2010), I Not Know Gun Was Loaded Sorry (2005), and I Burn Pinecone and Throw In Your House (2009). And we all know the connotations of male danger: murder, war, familial abuse. Lynch never seems to throw in a Medusa or Medea. His drawings and paintings probably seem less heightened than his films because they lack dissonant music and can’t show a character’s sexual spectrum. And I like your comparison to Magritte’s The Treachery of Images. Not only does Magritte address the concept of a real pipe, he also refers to the famous, and unsubstantiated, Freud quote on sexual archetypes, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” His painting The Lovers also relates to this in that the faces covered with cloth were possibly linked to the teenage Magritte’s discovery of his mother, drowned by the river, with her skirt pulled up over her face.

I Burn Pinecone and Throw In Your House, 2009. Mixed media on cardboard, electrical system, bulbs framed behind plexiglass, 72 x 108 in. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Karl Pfefferle, Munich, Germany

WS Remember Audrey Horne’s little brother, who is only on camera for a couple of minutes, shooting flamboyantly colored bison cutouts with a bow and arrow?

CF I don’t remember that, but it sounds pretty funny.

WS Like Twin Peaks, which is just filled to the brim with damaged men, the PAFA show exhibited a similar willingness to put one’s own masculinity on the line for critique. For me, this connects to Lynch’s frequent allusions to the genre of melodrama, an arena in which gender roles exist so forcefully and obviously.

CF I agree. Lynch’s Inland Empire has these really weird, funny scenes of Laura Dern on the sofa watching a large group of oversexed teenage girls in hot pants doing aerobic line dancing around her. It was a moment of hetero-American pie, porno, and lesbianism—as if they were in a Young and Restless-type soap gone wild. The film starts as a murder mystery on a movie set, but by the end it’s just Dern and the girls. Everyone else disappears, including the plot. A funny skewering of Hollywood.

WS Despite Lynch’s insistence to the contrary, it seems to me that his work is intensely aware of art history. I see Kiki Smith, Man Ray, Georges Bataille, Jasper Johns, and so on. This isn’t to say I think he is derivative, rather, it seems to be a very smart commentary on painting, drawing, and sculpture in his contemporary moment. How can we make sense of this, considering the fact that Lynch hasn’t found a place in art history outside of film?

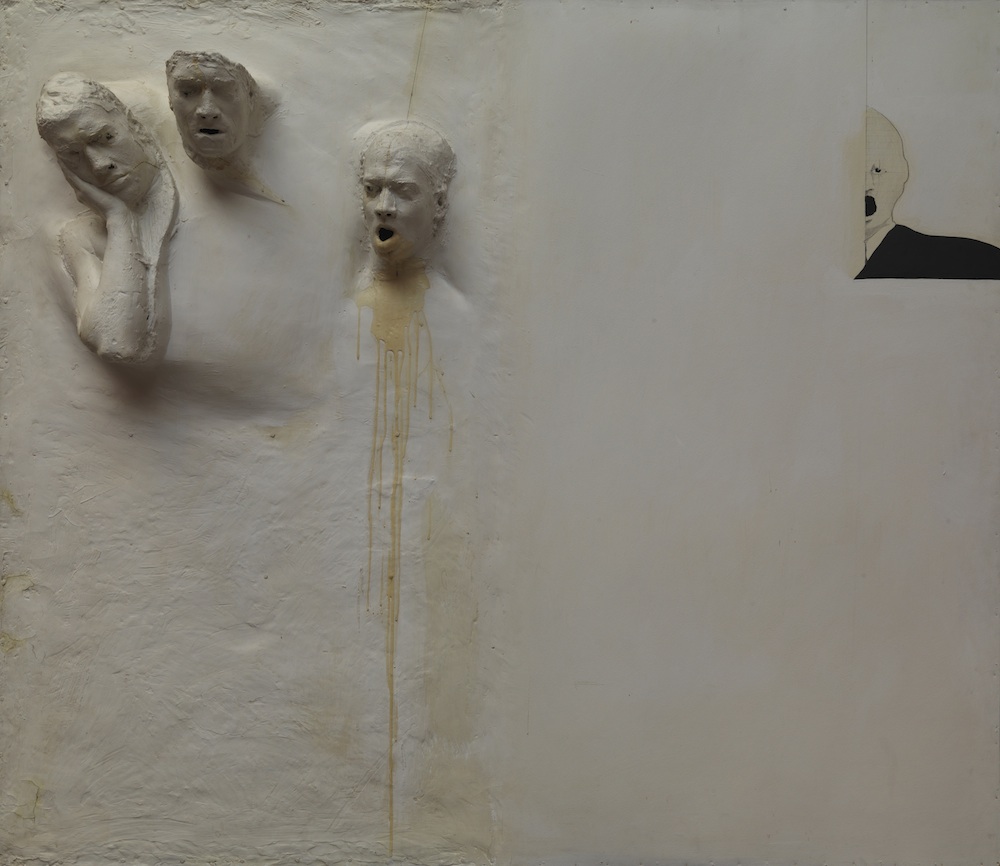

CF Maybe it’s possible our society can only laud a person in a single category. Had Warhol received an Oscar maybe Lynch would have had a show at MoMA. Maybe he just hasn’t made enough large paintings yet. You’re probably right that Lynch is very aware of art history. There’s a visual similarity to Francis Bacon, “outsider art,” and cartoon work, which I mean in a positive sense. Maybe this reticence is due to the fact that he did not stay at any of the three art schools he attended for over a year. In this show there is a drawing titled PAFA is Sickening (1967). His paintings remind me of Edward Kienholz, Bruce Conner, and Llyn Foulkes. Lynch’s first film (made while at PAFA) was also a sort of painting—a sculptural relief of three heads, with a looped projection on top (Six Men Getting Sick, 1967). Lili White sent us an experimental film by Bruce Baillie, of a white picket fence with “All My Love” sung by Billie Holiday. Does it seem like the referent for Lynch’s picket fence in the beginning of Blue Velvet?

WS As I watched the Baillie film, I was reminded of how the picket fence acts as an interspace wherein middle class subjectivity is created. The white picket fence is an archetypal measure of success in the United States—at least, that is what has been fed to us by Leave It to Beaver. But there is something sinister about it since it keeps people out. In order to establish middle-class respectability, you have to erect a wall in order to keep out all those identities and subjectivities that would threaten it. Lynch seems to point exactly to that fearsome place, that psychic arena, wherein the American Dream falls apart. Lynch and Baillie both pan toward the sky, as if they are looking for something elsewhere. I wonder what it is.

Screen for Six Men Getting Sick. Fiberglass, resin, acrylic, and graphite with masonite panel, 71 5/8 x 82 ¾ x 10 in. Collection of Rodger LaPelle and Christine McGinnis, Philadelphia, PA.

CF As in, “Let’s look away from the obvious danger-in-the-making?”

WS Yes, exactly. Suburban life has a uniquely terrifying place in his world.

CF Lynch has made a lot more artwork than the ninety pieces on view at the Academy. He has made photographs that resemble film stills, like Untitled (Little Girl #1) with a young girl in a blue dress and a man’s arm on the left, both holding tongs near a grill with red flames. Or,Untitled (Just War #3) with a very young girl on the ground looking dead or worse. There was a dissolve in Fire Walk With Me that, for a second, looks like a moving painting, where a car windshield with the words “Let’s rock” written on it (Isn’t this both a rock’n’roll and US military slogan?) dissolves to water. I also thought the photograph of the room with the door in Fire Walk With Me looks like a Lynch artwork. It’s the photo the old woman and little boy give Laura Palmer. The boy looks like a Lynch midget.

WS That’s Lynch’s son!

CF Really? I found Fire Walk With Me incredibly disturbing. Not many directors deal with incest. Would the impact of the murders and sex be different had the abused been men? Is Lynch’s Fire Walk With Me closer in intention to Pasolini’s Salo or Gerard Damiano’s The Devil in Miss Jones? After I rented the Twin Peaks TV series, it occurred to me that he was more interested exposing the myth of the civilized society than concern for the criticism it would engender. Do you think his movies are just violent entertainment with an artistic twist or a serious contemplation of the male psyche?

WS This is where the question of responsibility comes up. Blue Velvet and Fire Walk With Meare intensely gruesome. There is no sense of moral redemption. Lynch’s paintings are the same—they feel like violence for the sake of violence. It seems that his work lacks the expressly critical dimension of Pasolini, though Salo is definitely on a different scale of horrible. There are several articles from the 1990s by feminist authors about how sexist Twin Peaks is. Lynch’s work is predicated on violence against women’s bodies, but there is also a very frail and fragile male ego on display. Where is the line between ironic and incorrigible? What can be said for the fact that Lynch’s films could be a trigger for people who have experienced real sexual violence?

CF Lynch’s films probably are emotional catalysts, but then so is our daily media. Yes, his films—more so than his art—contain scenes of brutal predation; the fragile male ego becomes dangerous, a small animal when cornered. Fear of losing one’s identity can turn men, and sometimes women, into killers. I think that with Fire Walk With Me, Lynch brought to light what Freud had to shelve: that incest was traumatic and common, that the abuser was most likely a victim of abuse, and that violent abuse is so debilitating that it causes disassociation from oneself and often amnesia. Maybe, that’s why Lynch has abandoned the narrative for free association.

WS I’m really interested in the Black and White Lodges being spiritual realms. Aesthetically speaking, why is the “red room” saturated in Art Deco and antiquity? This is a different aesthetic than his paintings certainly, which have very little color. It’s almost as if the black lodge recalls the aesthetic ideal, where one learns to draw from the nude. This also recalls the reification of gender roles in the French Academy. Women, of course, could not draw from the nude for fear of “contaminating” them. Laura seems to be the distillation of these fears—a woman whose attempt to gain autonomy over her sexuality leaves her dead at the hands of her father, a simultaneously art historical and societal killing.

Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House, 2009. Mixed media on cardboard, 72 x 108 in. Courtesy of the artist.

CF Why Art Deco? Could Lynch be thinking of this European architecture movement, known for its luxury, glamour, and faith in technological progress during the rise of Hitler, as drenched in blood and strangely parallel to the US now? The red and the black, could it be Stendhal’s “The truth, the harsh truth?” Are the White and Black Lodges from Grimm’s fairy tale “The White Bride and the Black One?” Or is it that Lynch recognizes that most of us see everything in dichotomies? The character of Laura struggles to recognize the reality of her abuse and the identity of the abuser. She never enlists help, and she confronts her insane father alone. Had she been two feet taller and 100 pounds heavier, the confrontation might have been successful.

Coleen Fitzgibbon is an experimental film artist based in NYC. She has screened her work at international film festivals, museums, and galleries, including New Museum, Ft. Worth Modern Museum, Salon94, Louis B. James Gallery, MOCA/LA Film Forum, Austrian VIENNALE, TIFF, International Film Festival Rotterdam, BERLINALE, MoMA (NYC), Palais des Beaux Arts (Brussels), Institute of Contemporary Art (London), DeAppel (Amsterdam), Subliminal Projects Gallery (Los Angeles), Anthology Film Archives, Light Industry, and Exit Art (NYC).

William Simmons is a PhD candidate at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and his work has appeared in Artforum, frieze, Aperture, and Modern Painters.