In the 1970s, American universities and art schools began to include filmmaking in their curricula. Generally, the charismatic teachers they hired to conduct such courses were a generation of avant-garde filmmakers. They were mostly brilliant autodidacts (such as Stan Brakhage, Ken Jacobs, George Landow a.k.a. Owen Land, Hollis Frampton, Lawrence Jordan, and Ernie Gehr), or, if they had formal educations, they had taught themselves cinema (Robert Breer, Larry Gotheim, Paul Sharits, and Tony Conrad were examples of this).

From these schools there emerged the first generation of artists who had been taught how to make avant-garde films. Most of those who survived as filmmakers became teachers themselves: Saul Levine, Marjorie Keller, Bill Brand, and Louis Hock all came out of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. They were steeped in the history and aesthetics of American avant-garde cinema; in short, they worked within an artistic tradition.

Coleen Fitzgibbon shared their training at the Art Institute but not their aspirations. She did not see herself as a filmmaker but as an artist who made, or used, cinema among other media. She did not aspire to produce a corpus of work like that of her teachers. She was familiar with the parameters of the avant-garde cinema that her peers had inherited, but she was not emotionally committed to it. Her ironic stance was her strength. In a few years in the early 1970s, she made a series of radical films and then put aside the medium to focus on other modes of artistic invention. Her FM/TRCS transformed the then-dominant genre of cinematic self-portraiture into something visually unique, from which the indices of selfhood had been erased. Then, in an astonishing gesture, she made the most reductive of all flicker films, Internal System, exposing the color temperatures of the projection apparatus itself and the auditory “heart murmur” of the motionpicture camera as it exposed film. Later, at a time when Michael Snow, Frampton, and Landow were exploring the power of words on the screen, she found a way to make utterly original films out of microfiche.

Two generations of film students passed through the schools. The second of these included young scholar-filmmakers interested in film preservation and in the exhibition of lost or forgotten filmmakers. The rediscovery of Fitzgibbon’s philosophically radical cinema of the 1970s, 30 years later, reawakened an enthusiasm for the medium in the artist herself, who then embraced the latest technologies, including the iPhone, to make new films and reshape her “forgotten work.” We talked of these matters in January 2013.

P. Adams Sitney I didn’t know that you went to Boston University! Did you know you were going to be an artist?

Coleen Fitzgibbon No, my dad wanted me to be a secretary. He said, “You’ll never make money in the arts.” So after six months of writing 25-page papers, I realized I wasn’t cut out for the humanities and transferred to the art department. It was Renaissance training—life drawings, anatomy, perspective . . . In ’69, I had a summer job in Southampton, where I met Roger Welch, Dennis Oppenheim, Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, gallerist John Gibson, and his wife, Susan.

PAS How’d you meet all those people on a job in Long Island?

CF I was the personal assistant for a Prokofiev musicologist named Florence Jonas. One day I biked to the Parrish Art Museum and there was Roger Welch organizing an avant-garde art exhibition. “It’s gonna be great, you’ve got to come back,” Roger told me. Even the DeKoonings showed up.

PAS This implies that you were already interested in art before you went to BU.

CF My mom, a painter and biologist, encouraged me early and my high school art teacher, Gerry Rinaldi, a Vietnam vet, took us to every modern art show in the Tristate Area. My dad was more pragmatic about surviving as an artist.

PAS What did he do?

CF He was a first-generation American. After leaving Ireland, his parents worked their cousin’s farm in Illinois. The GI bill allowed my dad to get his PhD in education. My mother’s family moved by covered wagon to Illinois in the early 1800s.

PAS He was a teacher?

CF Teacher, guidance counselor, and intelligence-test salesman, then publisher. We moved ten times by high school through Illinois, California, and New York. I attended BU for three years, then transferred to the Art Institute of Chicago, and in 1973 I went to the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York.

PAS You went to the Art Institute as a sculptor?

CF No, I was painting in Boston. Chicago offered film and video so I tried it.

PAS You didn’t have to be in a department?

CF It seemed very informal. SAIC was small and had young teachers, and very little money. Their then laissez-faire attitude was similar to that of the Whitney ISP (we’re talking early ’70s). I took film with Stan Brakhage and George Landow and video with Phil Morton. They had a lot of visiting artists—Carolee Schneemann, Lynda Benglis, Alex Katz, Mary Heilmann. Landow’s class was my first film class; three weeks into it, after watching hours of educational library films, I asked the quiet teenage projectionist when Landow was showing up to lecture. Of course this was Landow.

PAS There’s this story that you participated in kidnapping him at one time?

CF (laughter) Christa Maiwald and I were friends at SAIC and often collaborated making art. George really liked Christa, and when his birthday came up we told him to expect a special day. We planned to bring him to a fortune-teller, to a stripper, and then back to the house for cake.

PAS His birthday was September 10. He was my oldest friend. His recollection of the story was, “Characters out of my film suddenly came to kidnap me . . . ”

CF Right! We wanted George to come with us without telling him where we were going. Christa and I knew two students George didn’t know—big guys just out of Vietnam who had a car—so we had asked them to escort George on our adventure. They showed up wearing black Lone Ranger masks and grabbed him from behind, blindfolded him, and started dragging him to the car. Skinny as he was, George wrestled out of their grasp and disappeared for a week. We felt terrible! Later George told us he thought his new film characters (who also wore masks) had come to life.

PAS Well, actually it was something he would more or less brag about later.

CF Oh really? Thank God! But I did hear he died penniless.

PAS He died penniless, and he was always very sick. He died in Los Angeles after a massive stroke. He was trying to make a film, and one day he was found dead in his apartment.

CF Most artists in the US live on the edge with no support. I really like Landow’s films; they have a visual language that can’t be expressed in words, a juxtaposition of banal images that become Zen koans.

PAS Oh, he was brilliant and he was a complete original. We were born in the same apartment building. I knew him from the time we were one month old. He entered cinema at my encouragement when we were teenagers.

CF I find it so unusual that you guys grew up together in—

PAS New Haven, Connecticut.

CF Right by Yale. I remember reading that when you were ten years old, you realized at Yale you could—

PAS —enter classrooms. I could just go in. They thought I was the son of the professor, or the professors thought I was the kid of a graduate student! In those days graduate students tended to be married. At that time I was the only white male in my grammar school, and I was street smart. I would go into the chemistry lab to build rockets or go to the geology department to collect rocks. I knew how to work my way into these places.

CF Had you and Landow seen Stan Brakhage films by then?

PAS We had just begun, but in those days, Brakhage was making much straighter films. This was long before Mothlight. Landow was extremely radical.

CF George’s style of teaching was to project films without comment; his only instructions were to get a camera and shoot—I bought a 16 mm army cartridge camera where you slide in a three-minute cartridge. Later, in 1979, I learned professional film production at NYU and on the job.

PAS When did you start making 8 mm films? Was that in Boston?

CF No, in Chicago—before that I had a phobia about everything mechanical. Olden Camera sold me the 16 mm cartridge camera and later an 8 mm, which was cheaper to use. Sadly I didn’t make prints then because of the costs. I showed the original (reversal) films.

PAS I don’t know if I’ve seen many of these 8 mm films. I saw the film you made with Margie [Marjorie Keller] and Saul [Levine].

CF I recently found raw footage that Marjorie, Saul, his grad class, and I shot in 1976 with the Super 8 Leacock system. We never edited it, so I made a version called Make a Movie. I used to film with 8 mm on the Chicago streets pushing Tri-X film if they were night scenes, and when I got to New York, I made a series of Super 8-sound street interviews in Times Square. While I was in Chicago, we showed each other works in progress constantly.

PAS Do you mean you and Saul and Margie or a larger group?

CF Saul Levine, Marjorie Keller, Jim Curtis a.k.a. Diego Cortez, Bill Brand and his then wife JoAnn Elam, Christa Maiwald, Louis Hock, Seton Coggeshall, Ruby Rich, Gunner, Ramon White, and a few others. Summers, Diego and I projected experimental films on the outside wall of my building, and our neighbors who worked in the factory across the street brought their lawn chairs. We also went to Ruby Rich and Gunner’s, watched films and drank purple-haze punch. I first saw Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising at a Ruby and Gunner party, and was so inspired, I sent Anger a letter and a box of 3-by-5-inch glass negatives of architecture. The unprotected glass arrived in shards, and he sent a cryptic response asking if my intention was to send him images or splinters of reflection.

PAS Did you ever meet?

CF Briefly at SAIC when he came as a visiting artist. I first saw Anger’s films in Brakhage’s film history class. Brakhage was the Scheherazade of the experimental film world; he showed almost 200 films (almost all by men) the two years I was there.

PAS Well, there were mostly films by men, but he would have shown Maya Deren and maybe Gunvor Nelson, although there weren’t many works by women available on distribution.

CF Why not? And yes, he did show Deren, Nelson, Leni Riefenstahl, and Marie Menken.

PAS It was this boys’ technical thing. But Brakhage was never someone who didn’t want to promote women. He was always big on Joan Mitchell as a painter, Gertrude Stein was his favorite poet, and his then-wife Jane had a big influence on his work. He was always promoting Marie Menken, for example. But it was only in the ’80s that people did research to find women like Jane Congor, whose films had never been in distribution. Some of the by-then-older filmmakers began to show up again. But largely it had been a boys’ thing to make films.

Among your early films is Henry Darger’s Room from 1973?

CF Yes. Near the end of my stay in Chicago, Michael Baruch, a SAIC student of Nathan Lerner’s (Darger’s landlord), asked me to film an apartment where they had found artwork and wanted to get an opinion as to whether to save it.

PAS Oh, this is when they had just discovered Henry Darger’s stuff?

CF Exactly. I had one 100-foot roll of Super 8, so I single-framed items in Darger’s apartment. Garbage came up to your knees, but in it were huge books of writing and beautiful but bizarre cartoon watercolors of little girls. Everyone agreed it needed to be preserved. In the mid-’90s I started a short documentary on Henry Darger with Michael Thompson and interviewed several people related to the Darger mystery. Michael and I had a falling out so we gave footage and research to Mark Stokes, who made Revolutions of the Night, the film about Darger, in 2011.

PAS And you made a film about getting dressed.

CF In Chicago I tried hallucinogens and sort of freaked out. Later Jack Smith told me I had agoraphobia. I couldn’t leave the house; it was like Exterminating Angel except I was alone. So I filmed daily activities that I was obsessing over, edited them into a parabolic structure, and titled it Frame of Mind.

PAS So you had this footage of yourself getting dressed?

CF Yes. I decided to obscure the images to parallel my physiological state—I was hearing and seeing weird peripheral sounds and movements probably due to psychedelic flashbacks, but who knew then? I took the original 8 mm Frame of Mind and optically printed it to 16 mm, using high and low contrast mats to blow out the images. It was retitled FM/TRCS.

PAS That was the first film of yours that I saw. I was on the jury at the Knokke–Le Zoute film festival in Belgium in 1975 and your film was so unusual and so distinctive that it was one of the few films that the jury quickly agreed to give a prize to. The head of the festival and the museum, Jacques Ledoux, really believed in the word experimental. And for them this film was almost a kind of laboratory experiment.

I recently saw your transfer of I. S. Migration (1975/2010). I found it much more challenging now than 30 years ago—I think you were projecting original footage back in the ’70s.

CF Yes, I projected originals then. The new version is a digital transfer of Internal System, supersaturated and showing the optical track and digital-transfer raster in the frame, continuing the idea that all processes are visible. I had only shown Internal System once since the initial 1975 Knokke screening when most of the audience left the theater.

PAS But that wasn’t unusual at a festival. There was an enormous social scene outside and a lot of draw outside the auditorium.

CF Yep, it was a casino with huge chandeliers, Pierre Clémenti with entourage, Otto Muehl and AA-Kommune (Aktionsanalytische Organisation), gamblers, free alcohol and food. . . .

PAS Shortly after that you got the job working with microfilms, didn’t you?

CF From 1974 to ’79 I worked part-time for Rick Van Auken’s Information Technology Center microfilming public documents (warrants, bankruptcies, debts, etc.), learning computer language and storage and retrieval machines. Rick had been a ’60s Apollo space-program analyst.

PAS But your films there weren’t made with a computer?

CF No, they were on microfilm. My first job experience was filming documents of warrants in the New York Supreme Court basement on a 16 mm microfilm camera for the court system.

PAS So you made your own copy of the stuff?

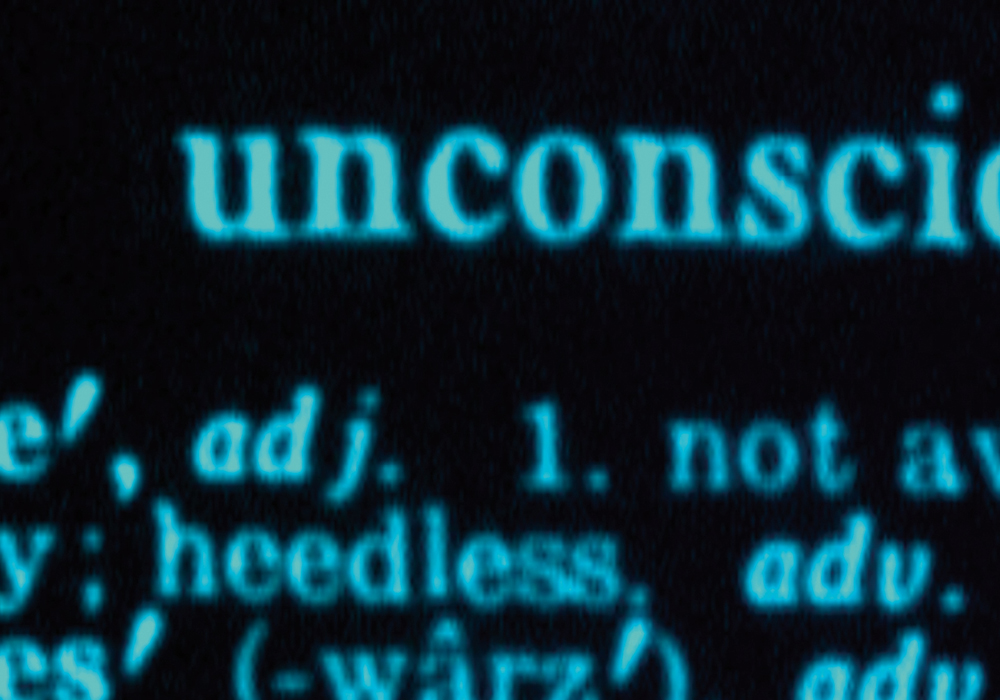

CF After-hours, I made my own text films on the microfilm camera. I filmed magazines, newspapers, dictionaries, documents—which became the films Time Magazine, Der Spiegel, Daily News, Dictionary, and Document. Showing microfilm is very subliminal because the microfilm camera frame films the equivalent of three regular frames so you see the film—

PAS Triple frame.

CF The faster the film moves through the frame the less you visually retain until you reach a consciousness threshold where the sensation is remembering something you can no longer recall.

PAS And what you’re seeing are whole pages of text? You’d have to be able to read awfully fast.

CF It’s a version of speed-reading. It’s best to let the text flow over you because continual text is stimulating to the point of exhaustion. We navigate daily through hundreds of signs, newspapers, magazines, websites, and product ingredients. In ’73 I was an American tourist traveling through the tunnel from West to East Berlin and had an epiphany of life without text. There were no signs in East Berlin, not even on restaurants. Nothing, only bare light bulbs. Then you cross back over into West Berlin, and it’s like the States.

PAS I’ll note that you associated this with Wittgenstein’s Notebooks and his Philosophical Investigations.

CF I spotread Philosophical Investigations, Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality, and a lot of Gertrude Stein’s modalities of consciousness. In the text film Dictionary, where words starting with un- and re- are filmed, some words you can remember, others you can’t. Word recall is subjective. In 1970 I visited Dennis Oppenheim’s show in Boston where he had a parrot tied by its foot to a perch and next to it a tape recorder playing a loop of Dennis’s voice saying, “Yellow.” After a week of “Yellow,” the parrot attacked the audiotape and ate it, digested the content, and survived. (laughter) I think everyone in the New York art world was reading Wittgenstein by the ’70s.

PAS Around that time you got very sick, if I remember. You had a heart problem, and you were in the hospital?

CF In 1976. At the Knokke–Le Zoute film festival, I had been partying late every night like everyone else. On New Year’s Eve, people were dancing in the streets until the sun came up.

PAS I was stuck in the jury room.

CF Well, okay, all the Belgians and I were out dancing. The success of FM/TRCS sort of freaked me out and by the time I returned to New York, I was run-down and sick and was in and out of hospitals that year. You and Margie came to visit me in intensive care and your jokes were setting off the ICU monitor!

PAS And the nurse came running in! Because I was making you laugh.

At that time you stopped making film.

CF Yeah, I was sick and had no money. I went to live first with Marjorie Keller and then (through Betsy Sussler) with Jacki Ochs and went on welfare for a year. Thank God for friends. I started doing more collaborations with others artists after that.

PAS You did something else around that time that I didn’t see, but Ken Jacobs said it was absolutely sublime. It was a performance space somewhere where you hired a cleaning crew. Can you tell us about that?

CF That was at the Clocktower, where Alanna Heiss invited artists to do performances. I split a night with Michael McClard whose performance before mine was going to fill the space with sand. I asked him if he was going to clean it up and he said no. So my performance was to turn on a radio and have a six-person work crew come in and clean up while the audience sat in the bleachers drinking, talking, and waiting for the next performance. I was inspired by a piece that Diego Cortez had done in Chicago several years before.

PAS Many people thought it was the greatest performance of the decade!

CF It was subtle.

PAS No, they thought that it was great because real workers did a real job, and they knew what they were doing, unlike most artists. Did you do other performances of that sort?

CF Many of my performances were similarly collaborative. In 1975 Saul invited me to show films, and I sent James McClaine, recently released from prison, to SUNY with a film, Letter of Introduction. He lectured on prison reform until the audience left. Robin Winters and I collaborated as X&Y International Artists in Holland in 1977, and one of our performances was Take the Money and Run, where we robbed the audience and made them collaborate to get it back. At Sarah Lawrence, invited by Bill Brand, Anya Phillips and I did a multimedia performance, Alternative Employment for Women, where I interviewed Anya about dancing in strip clubs. In 1979, I was a partner in the Offices of Fend, Fitzgibbon, Holzer, Nadin, Prince & Winters, and we approached the UN to offer our “function & pleasure” art services for their labor problems. (They did not accept.)

PAS If I recall, at that period you were very militant on questions of women’s art.

CF Was I?

PAS Yes. We’d be going to such and such a screening, and you wouldn’t want to come, saying, “I’m not interested in seeing a bunch of films by men.”

CF Really? I did that?

PAS Reasonably, you weren’t alone in the early 1970s in feeling that way.

CF In the ’70s, it felt like films made by women were less likely to be accepted into festivals.

PAS That certainly wasn’t true of Jacques LeDoux, who was the first person in the world to have an all-women film month at the Belgium Film Archive.

CF LeDoux was different, and you were not like that.

PAS But I wasn’t looking for women to show, which many of my more progressive colleagues were. I just felt as though I was gender blind, which isn’t exactly the same thing, and which at the time wasn’t considered particularly progressive. So tell me: What was Colab?

CF Colab was short for Collaborative Projects, a group of 40 to 60 filmmakers, artists, actors, and writers. We’d come together in downtown Manhattan to make art as a group. At the end of 1977, Betsy Sussler, Eric Mitchell, and Michael McClard had done a small filmzine called X Motion Picture Magazine. This was one of the initial inspirations to work collaboratively which led to one more issue of X, live Manhattan cable shows All Color News and Potato Wolf, The Real Estate Show and The Times Square Show, as well as related spin-offs like ABC No Rio, Dog Show, Just Another Asshole . . .

PAS Why do you call it The Times Square Show?

CF It was an art show in June 1980 in Times Square, in an abandoned massage parlor on 41st and 7th Avenue with almost 100 artists including performers, musicians, and filmmakers, organized by Colab.

PAS You rented the building?

CF For two months. John Ahearn and Tom Otterness found the building and all of Colab voted unanimously to do the show. It was open for a month, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and was the largest Colab show produced. It was wild in the early morning hours.

PAS And The Real Estate Show?

CF On December 31, 1979, we took over an abandoned Con Edison building on Delancey Street and filled it with art. On New Year’s Day the police came and shut it down . . .

PAS You mean you just invaded the building?

CF We cut the locks, put in the art, and invited people to come. Joseph Beuys came to the opening with Ronald Feldman. Word got around. The police came and locked the building with the art inside and a Colab subcommittee negotiated with the city; Rebecca Howland and Alan Moore worked on the final agreement to get a building to house art shows in. This eventually became ABC No Rio at 156 Rivington, which still exists and was set up to have revolving groups of people running it.

PAS As a member of Colab did you primarily see yourself as a filmmaker or a performance artist?

CF Hard to say about the Colab years. I like to work with moving images but I also make static images in different media. I’ve been making digital prints lately, and although my work is shown largely in film venues, it also goes to galleries and museums. In 2012 I had work in the Viennale in Austria, at the New Museum, and in Times Square Show Revisited at Hunter College. Usually the work is shown digitally.

PAS I have a lot of problems with digital work. One, I’m not wild about the look of it, the pure sensual look of it and two, it seems to be absorbed into a culture of distraction.

CF Well, yes. We live in a culture of distraction, don’t we?

PAS Well there’s something called fighting it.

CF Increasingly it’s difficult to find the film stock, equipment, and labs to make celluloid films. Very few places project them. When I show films in exhibitions at the New Museum, MoMA, or galleries, the films show continuously on kiosks—visitors stop for the amount of time they want and listen on headsets. No more sitting through the entire film in a theater.

PAS As a person who has been teaching for 50 years, what I see is even worse, where the students want to do their work while on Facebook and YouTube. I can’t exist in this environment anymore. I don’t allow computers or cell phones in my classroom. As a result, my enrollments get smaller! But I’m about ready to retire from the world of . . . you know, it seems to me that you can’t get into an Ivy League school anymore without ADD.

CF I was at the Art Institute of Chicago as a visiting artist recently and while the grad students were talkative, the undergrads were sound asleep or on their iPhones. They asked why my films were so long. Twelve minutes? They preferred three minutes.

PAS Exactly! That’s part of the digital problem. The structural cinema involved a real commitment to time. Something’s going to happen in the next 30 minutes to five hours that, if I sacrifice my time, could be of extreme value—a whole different shift of temporality. And that’s a very hard sell with digital. It’s not just keeping others’ attention. It’s the idea of wanting to give the gift of your attention. That’s what a Warhol or a Snow film asks you—I’m not going to instantly please you or hold you like a page-turner, but if you give me this gift, I will reward you.

CF Well how do your students react to Michael Snow or—

PAS Well, it becomes a highly specialized thing. I began teaching thinking I’d be a teacher of Greek or Sanskrit, and I’ve ended up one, in the sense that the kind of students who really want to study film are as rare as the ones who want to study ancient Greek. But I’ve also lived through a time when you had to beat the students out of the room. There was a period where students were so interested in film that they would flock. It has simply disappeared.

Let me ask you about the long period when you weren’t making or showing films.

CF I stopped making much art from 1982 until 2006 and worked commercially, first as a camerawoman for CNN and then as a producer for commercials, music videos, industrials, documentaries, and independent narratives to make money.

PAS And what brought you back to the art world?

CF I had the time and the money to make art again, so I have been showing old and new work. In 2006 filmmaker Sandra Gibson, in NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation program, began to help me organize the 16 mm films. We made prints and transferred them to digital; she made archival notes and wrote her thesis on Internal System. Both Sandra and her partner, Luis Recoder, good filmmakers in their own right, were instrumental in promoting exhibitions of my old films in the US, Europe, and Korea. It was great to work with her, though she is a film purist and not a digital enthusiast.

PAS I sympathize with that. Very few have not converted to video. There are very few holdouts—Robert Beavers, Nathaniel Dorsky, Peter Hutton . . .

CF Hutton’s films are really beautiful. I saw some Snow videos when I went to the Toronto film festival; I thought they were interesting. I edit on the computer myself.

PAS Nobody I know does sound on the old system anymore.

CF Do you feel there’s a problem sometimes with writing about film because it’s language versus visual images?

PAS It’s language. It’s no substitute. I write about film, but I’m just writing words, thoughts on film.

CF And you coined the word structural.

PAS Oh, well the word structural isn’t mine, but I do use that term. After one year at Knokke—Snow’s Wavelength won the grand prize—there were several films that were single shots or loop printed. I saw something different happening. And I thought, Well, you have to see the structure of the whole film to see what the film is; it isn’t just by following it moment to moment. So I just used that term. It was unfortunate because it got confused with the French anthropological thing; I wanted a term for those kinds of extended, or repetitive, or reductive, or simplified films that I saw all coming out at the same time. And then another confusion arose when I saw Brakhage and Markopoulos moving in that direction. I defined structural film as an emerging genre, but people wanted to talk about a new group of filmmakers as if Landow, Frampton, and Snow were structuralists, as if it were their style rather than a generalized style that I was seeing occurring in many different directions. But that’s just a critical perspective. I write words for people who want to read things about these phenomena—they’re not the things themselves. But it also makes me see things better by writing about them.

CF Without critical film writing, who would know that experimental films exist? So many great ones have already fallen into obscurity. There is no advertising for them as there is for Hollywood films.

PAS Tell me about your recent films and your current projects. How has technology influenced them?

CF Lately I’ve been working on projects that are digital color fields in time using After Effects. ColorFAST, not yet finished, is one such work. It is like an abstract acid trip with over-the-top colors and patterns materializing. SYBAR is an After Effects transmutation from Dictionary. I’m also shooting small sketches with my iPhone, like Beach, Rose, and Flower, which are edited on iMovie. Land of Nod was shot on tape in the ’80s on the Lower East Side streets of Manhattan, transferred to digital, and finished this year on Final Cut. Digital allows me a larger palette to create images and colors; it also gives me the ability to see my work in different modes—on the Internet, in digital projection, on televisions and computers. It allows me to see how they change a film’s appearance. I like having my films on the Internet and getting feedback from viewers around the world. Film and digital are both useful. I just saw Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (of the 1945 Bikini Atoll test) in 35 mm at Anthology Film Archives; it was great and may not ever be shown in any other medium. Now that 3-D scanning programs can remake the marble statues of the Acropolis, maybe moving images should be bronzed.