British artist and filmmaker Ben Rivers has made a series of dark, utopian films in which the protagonists, often male, have come to terms with their severance from society. Rivers’s feature-length film Two Years at Sea (2011), which was just released on DVD by Cinema Guild, was the culmination of his focus on the individual alone in the wilderness. For Rivers, utopia can exist as a personal state of mind or as collective thought. He takes from J. G. Ballard the belief that optimism can be born out of crisis and that the past can aid the future. Rivers often lives with the people he’s filming and scripts their actions, creating the illusion of documentation.

Ben Rivers’s work evolved from focusing on the lone individual to filming small insular communities cut off from larger societies, as in Slow Action (2010) and, most recently, the feature film A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness (2013), which was made in collaboration with US filmmaker Ben Russell. At a lecture hosted by New York MoMA PS1 this past summer, Rivers commented that “utopia in the present is cinema” where filmmakers “engineer circumstances” to construct their own model environments. For A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness , Rivers and Russell created a temporary commune where they lived with and filmed individuals gathered from various actual communes in Scandinavia.

Rivers has filmed on islands off the coasts of Africa, Japan, the South Pacific, and Scandinavia but finds the landscape of his own British Isles “comforting.” His interest in utopia, a concept first coined by Sir Thomas More, evokes a long history in England—from the time of the Enlightenment to British communes in the ’60s and ’70s. Ben Rivers may intuitively understand that small communities should retain their identities in the larger society so that the individual voice is still considered in collective thought.

—Coleen Fitzgibbon

Coleen Fitzgibbon The first film I saw of yours was Two Years at Sea at Anthology Film Archives last October, which my daughter brought me to see. It had just shown at the New York Film Festival and the New York Times quoted you saying that you made films not as end products but as a way to learn about the people you were filming—and how this affected your life.

Ben Rivers My filmmaking is in part a selfish practice of trying to have some good adventures while meeting good people. I always make films about people I like.

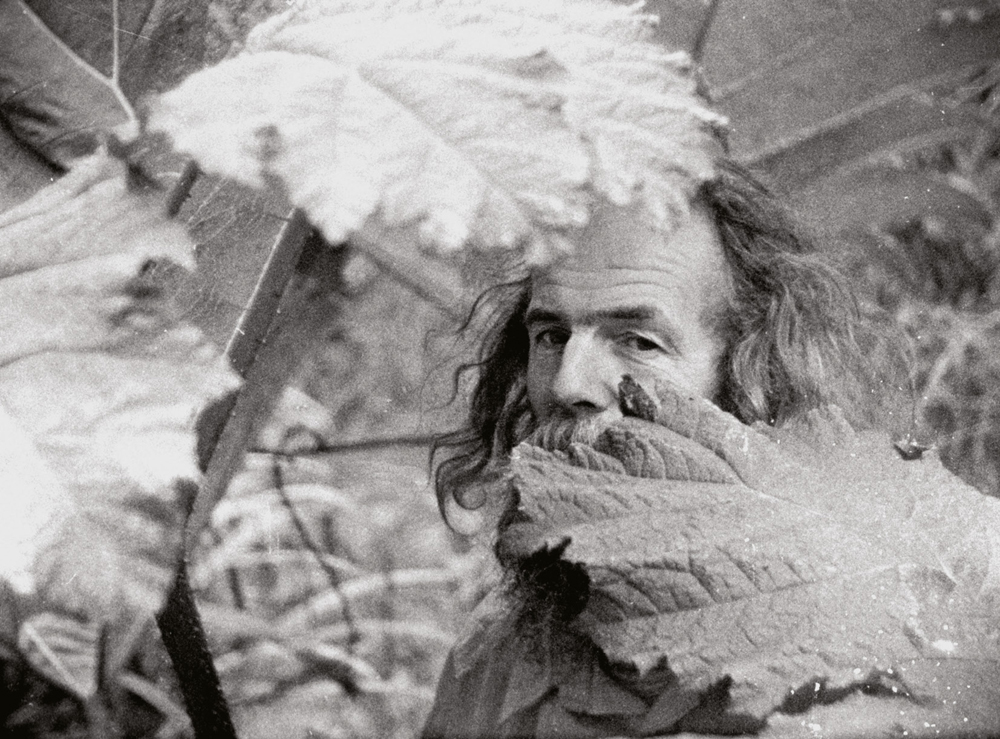

CF An earlier film, This Is My Land (2006), with Jake Williams, was expanded upon in Two Years at Sea as a fictional narrative.

BR This Is My Land was a more fragmented, observational document. I was watching Jake in his daily activities and filming what I thought was necessary and then piecing it together like a collage. But with the second film, Two Years at Sea, I wanted to be much more controlled because the film was meant to be feature length, so I had to think about the structure. Jake and I collaborated to make an exaggerated portrait of somebody very much like him, but not him. He is really noisy and chatty—he likes to talk, he likes visitors, and obviously there is none of that in the film, so it’s a fiction.

CF In Two Years at Sea, Jake never talks or sees anyone; he’s always alone and working in the woods.

BR I thought about scenarios which could involve other people coming to visit and then decided that it was a greater challenge to just have him not talking—so that it’s more a relationship between him, the space, and the landscape—and whether I could pull that off for an hour and half.

CF It was incredibly luminescent and compelling. I read that you hand-developed the film, which gave it a shimmering black-and-white quality impossible to get any other way. In the film, Jake is a wild character who has left civilization and gone into retreat.

BR Right, people do have these sorts of fantasies; that is how I ended up going to meet Jake in the first place. I was wondering about this idea of living in nature, something that I’ve thought about since I was a child. I was reading loads of literature based on this idea—especially Knut Hamsun, the Norwegian writer whose characters take themselves into nature, but it’s not bucolic or easy; they’re struggling with it. Hamsun wrote from the late 19th century into the 20th (and influenced writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Mann, and Franz Kafka), but the stories in the 1890s are the ones that had a big effect on me, especially Pan, which is about a man who goes to live in a hut in the woods. I was obsessed with this book and wanted to find somebody living like that in the 21st century. Jake Williams was the first person I tracked down. I then made a series of films about people living in the wilderness.

CF —Or men living in isolated rural settings who appear to be hoarders of cast-off objects. You spend weeks, often months, with the people you are filming. How do you concentrate in the midst of disorder and debris?

BR I look for this; it’s one of the things that usually causes a spark for me when I’m trying to find people—that someone should choose to live amongst the rubble and ruin of past technology is endlessly fascinating to me. The fact that this forms part of the landscape, and can be transformed into something new for the person hoarding it, also points to my continued interest in thinking sculpturally about space. Objects tell another story about the past that shapes part of the person’s psyche. In terms of my concentration, I think I would find it much harder to work somewhere that was clean and free of any kind of debris, somewhere bucolic, it wouldn’t fit my sensibility. I like roughness and dirt.

CF Are some of the people reluctant to be filmed?

BR If there were any sign of reluctance I wouldn’t make films with them. I’m only interested if it’s a collaboration. So there is usually a pre-filming period where I get to know people and make sure they are comfortable with me and my camera, and I make it clear that the films I make are not meant to be factual representations.

CF There is a clear trajectory in your work. Besides This Is My Land, there’s Astika (2006), which is about a man on an island in Denmark being forced out of his home. Then there is A World Rattled of Habit (2008), where Oleg and Ben Meschko, father and son, live close together—Ben in a rural trailer and Oleg in a house overrun with hoarded objects. Origin of the Species (2008) begins with a bubbling galaxy while an elderly inventor named S, who lives in a Scottish wilderness, muses over Darwinian theory. Ah, Liberty! (2008) shows an isolated farmhouse with kids at play in tribal masks, which could be a precursor to Slow Action (2010), a film about four remote islands. I Know Where I’m Going (2009) has a red-bearded man who says he is “just clinging on,” and finally, Two Years at Sea follows a protagonist (Jake Williams) living alone in his forest cabin with music from far-off places.

BR Each person or family takes the film off into another direction because they are distinct people. But I wanted to go back to Jake when I was thinking about making a feature film.

CF I heard he said, “Yes, go ahead and make me a star.” (laughter)

BR When I called to ask him to make another film, I thought he was going to say no, but it was quite the opposite.

CF The music was incredible in Two Years at Sea, with Jake playing a one-stringed instrument and his records. What was the title of the bawdy record that he plays in the film?

BR “The Sexton and the Carpenter” plays all the way through, even though it has quite a few jumps in it. Dave Goulder, who sang the song, gave us his blessing to use it. The Indian music, Jake had bought when he was traveling to India working for a shipping company. That’s where the title comes from: working two years at sea in order to save money to fulfill his dream of buying a house in the woods. Like the photographs that punctuate the film, the music and the title are clues to Jake’s past, but they are deliberately ambiguous.

CF The filmmaker Peter Hutton was a merchant seaman who shipped out to sea for seven years.

BR I like his work.

CF Was Slow Action made before you shot Two Years at Sea, or during that same period?

BR They kind of overlapped. I was finishing Slow Action when I started Two Years at Sea in 2009. The way I often work is to film, two or three weeks, come home, develop the film, and then go and film somewhere else. I prefer not doing one thing at a time, because I like the way projects feed into each other. One reason why Two Years at Sea is wordless was because Slow Action was going to be text-heavy.

CF I read that you worked with a writer, Mark von Schlegell, on Slow Action.

BR I had developed the film as an idea and was trying to come up with stories for the narrations, so I was copying bits from Victorian books—explorers traveling to find lost civilizations and utopias. It was going to be a sort of stolen language but I wasn’t happy with my literary skills. I came across a science fiction story by Mark von Schlegell called Venusia and asked if he’d be interested in working with me—I wanted him to write four accounts of four different island utopias. I never told him where I was going because I deliberately didn’t want him to illustrate too directly. It was a process of emails from me—giving him some ingredients, clues and books, and we went back and forth with reading lists quite a lot. He sent me back texts that I could change and edit so they fit with my images.

CF So you were filming on the different islands while he was writing at home; how did you like that process?

BR It was great; I’d like to do it again. Mark said he was nervous about it because there were more unknown factors on his side. He was happy with the result and said it was a nice experience because he felt free.

CF Do you travel with someone else, such as a soundman, while you film? I understand that you do the camera work.

BR During Two Years at Sea I had a sound woman, Chu-Li Shewring, who came with me each time I went to film Jake. So it was a two-person crew. For Slow Action it was just me because I didn’t need live sound. I had a pretty clear idea from the beginning that I wanted to use source sounds with the images I shot on location. Usually I record sounds myself, because I like how non-sync sound forces you to experiment with sound/image relationships in the editing.

CF In your films the theme of isolated individuals seems to expand to include remote cultures, such as The Coming Race (2006), based on an 1871 novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, where a new utopian society pilgrimages up and down a mountain for unknown reasons. Slow Action portrays four mythical future island cultures created after the seas rise, and Sack Barrow (2011) is an English factory’s final month, where aging workers play 1950s music, giving the sensation of an industrial island’s demise. The Creation As We Saw It (2012) seeks out inhabitants on an island in the Republic of Vanuatu, interspersed with funny stories about the beginnings of humans, fire, pigs, and a tragic tale of a volcano’s birth. Many of your films have been shot in Scotland, but for the filming of Slow Action you traveled to several faraway islands.

BR Well, Lanzarote was the first. It’s one of the Canary Islands and one of the driest places on the planet, a volcanic landscape of twisted and gnarly rocks that developed over hundreds of years.

I was trying to find a landscape that looked like another planet.

CF I saw your Slow Action exhibition and interview on the Picture This website. In your exhibitions the film is usually shown on a cluster of screens that have four different images. Were they from the same film, and did you think of the film as an installation while shooting?

BR I had two versions of the film in mind right from the start: one was a single channel where the narration fit deliberately to a particular island, and for this there are screening times so people can watch it from beginning to end. The other version was four channels where you see the four islands at the same time, one on each screen, but you only hear one narration at a time, and you don’t know which island it refers to. The authority of the narration becomes even more questionable, which is one of the thoughts behind the film—an unreliable encyclopedia of utopias of the future. The other islands were Gunkanjima in Japan, and Tuvalu, which is in the middle of the Pacific. The last one, where there are more close-up figures, is Somerset which is not an island at all; it’s a part of the west country of England where I come from.

CF Somerset in Slow Action could be a future fast forward from the factory in Sack Barrow. In many of your interviews you discuss your interest in mythical, future utopian societies. Utopia, written by Sir Thomas More in 1516, described a fictional island society in the Atlantic Ocean that was both “no place” and “best place.” More’s England was profoundly incapable of achieving social perfection. Somerset then is your utopian island?

BR You could say that. Somerset feels closest to my idea of utopia—which is a place that acknowledges that utopia is a place of flux, that in order for it to work it needs to be able to embrace its own impossibility while simultaneously embracing the need to keep trying. Slow Action refers to myths of the future, so since I was already fabricating the islands by composition and narration, it made sense for the last one, Somerset, to be completely fabricated. The filming becomes less distanced and at the end, even the narration, which up to that point has been authoritative third-person suddenly becomes first-person.

CF Slow Action was disturbing—with its scenes of palm trees swaying above industrial debris and deteriorating concrete island fortresses, a reminder of wastes to come. Its narration is subtly critical of modern colonial systems and Western civilization. It reminded me of a short film I made about the island of Manhattma called LES (1976) that employs similar narrative pseudo-fact. Your other island utopia, The Creation As We Saw It, looks like a 1920s film in the tradition of Tabu by F.W. Murnau and Robert J. Flaherty. It combines silent-film narration titles of a volcano myth intercut with close-ups of native people, shot on the island of Tanna (Vanuatu), but with a 21st-century critique. Seeing your films, I am also reminded of Werner Herzog’s Fata Morgana, Luis Buñuel’s Land Without Bread, Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus, and even a little of The Gods Must Be Crazy, in your use of documentary-like fiction.

BR I’m a big fan of all those films, because I think they question the documentary image. I’m kind of resistant to a documentary label because when you say “documentary,” people have an idea that you are trying to represent the world and provide information. I have no interest in doing that.

CF As soon as you turn on the camera, people act differently than if the camera wasn’t there, and you seem to incorporate this factor into your films.

BR If you’re Fredrick Wiseman and you’re filming in the same location for months, maybe people forget about you.

CF Wiseman’s Titicut Follies was shot in the ’70s in a Massachusetts mental asylum, and his subjects were often off in their unconscious and only peripherally aware of his presence.

BR I prefer the Jean Rouch approach, which is more collaborative with the people that you’ve asked to be in the film.

CF Yeah, when people are filmed surreptitiously, their faces reflect a flatness that comes from resentment or suspicion. But if you ask, they often respond with more energy and there is non-verbal dialogue. I used to film street people in Times Square.

BR I couldn’t be a street photographer.

CF You have made a number of gallery installations, like a recent one in Dublin at the Douglas Hyde Gallery, where you built shacks or cabins, inside which you showed your films on 16mm loops. You seem to show your films in galleries and museums as well as in film venues.

BR That’s right. I’m represented by Kate MacGarry gallery here in London. Film and gallery venues have equal weight for me. I think that films can exist in those two different ways because they change sculpturally depending on the space. Also, work is read differently because of the ideas and preconceptions viewers bring with them to the different spaces. The first cabin I made was for a piece called Sørdal (2008), which was a tribute to those early writings of Knut Hamsun.

CF I read that you once described your films as post-apocalyptic. They show people in retreat living in Arcadian landscapes filled with industrial garbage and unidentifiable junk, which is fairly terrifying. I suppose it’s the freedom to live without social constraints that creates joy?

BR It’s all about freedom, an idea I come back to quite often in my films: what the idea of freedom means. There is a sort of hope in the films I’m making, from looking at possible ways of being, further down the line. I made a film a couple of years ago called Ah, Liberty!

CF Yeah, I saw that. It was great: a strangely picturesque farmhouse set in the mountains, with kids swimming and playing in junk piles with masks—there are rainstorms, old cars, and farm animals.

BR Some people said it seemed post-apocalyptic because the people in the film are living around the ruins of no- longer used machinery, and that this time has come and gone so there is an element of unease and danger—but then there is also joy and hope.

CF Your protagonists have the ability not only to survive, but to meditate on aloneness constructively. That said, your films have a touch of the dark side. We The People (2004) is a beautiful black- and-white film without people, but with the sound of footsteps fleeing an angry crowd. It takes a while to realize the houses are miniature.

BR It’s a very beautiful miniature village in the south of England. I found this village and was told it wasn’t a good time to film because they had just taken out all the windows and doors to restore them—but it was perfect for me. (laughter)

CF How did you come to filmmaking, were you in art school?

BR I went to art school in Falmouth, in Cornwall. I went to do painting but changed to sculpture, and made 3D work and started running a film club. In my final year, I made a Super 8 film and realized that film was my medium—film in particular, not video—because of its physical nature. I like holding things, and with a moving film image you can have a tangible relationship. When you show film it can be a sculptural object as well.

CF It still has better resolution than video.

BR I’m not interested in resolution. I quite like rough-looking video. I quite like the look of Skype. There are other things in film for me—like the obstacles, the fact that you can’t watch film straight away, that there is more room for accidents to happen. Chance things can take the film off into a direction I wasn’t expecting, which is one reason I like hand-processing. You can never completely control it. There are many factors that change the film by the way it’s processed.

CF Terror (2006) and Alice (2009) seem to be your only videos. Have you made other “horror” films?

BR Terror is like the black sheep of the family. I’ve not made a video yet, apart from those found-footage films Terror and Alice.

CF They look pretty crisp for video.

BR Yeah, they were shot on 35mm originally, because everything is taken from found horror movies, but I edited them and show them on video. What I shoot is always film.

CF I went to see Tacita Dean’s show at the Marian Goodman Gallery recently and she had a book called Film from the Tate London show that she organized. You were in the book.

BR The book is about film and the danger of it disappearing. She invited several people who are involved with film to be in the book.

CF Your text in this book talked about the delay between filming and viewing the footage, and how that was important. You included a film still of the American filmmaker Ben Russell. Were you already collaborating by then?

BR Yes, we were, and I felt he had good reason to be in there as well as myself.

CF You’ve filmed in the British Isles, the Canary Islands, on islands in Polynesia, and in Japan, and then you went to Finland with Ben Russell to shoot A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness.

BR Actually that film is shot in Finland, a small island off Estonia, and Norway. The Estonia part is a very real attempt at a present day utopia, collective living.

CF Let’s talk about A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness. You co-directed/co-produced it with Ben Russell. You both shot and edited the film together for about two years.

BR We did everything together.

CF I saw your trailer for it and it looked great. Will you be showing this film in New York soon?

BR We hope so, we’re really happy with it. It took a while to do. There is an installation version and a feature-film version, so we just have to figure out who shows what, when—the premiere will be at the Locarno Film Festival. We edited the film down to 94 minutes, which is now final.

CF You and Russell also collaborated in the movie with the musician Robert A.A. Lowe. Is he the musician that plays in the black metal band?

BR Right, he is the central character. Some of my other films are investigations into a kind of utopia but they are one person’s utopia—to other people, they could be a complete nightmare. A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness is based around one person being seen in three very different kinds of places. In the first, he’s living in a small commune, and the collective doesn’t have a hierarchy or one dominant ideology or religion; they just want to live together.

CF Was it an actual commune or fictional?

BR It’s both actual and fictional, in the same way that Jake is actual and fictional in Two Years at Sea. This is what Ben and I both do, we mix actual situations with things we need, in order to make the film that we want. It’s about setting up the right conditions to make not a representation, but something that exists on the screen in and of itself. We lived with the people for almost a month so we could find the material we needed.

CF How was that?

BR It was great and transformative. The people had their own reasons for living together as a collective, but all of them were positive. The idea was that it would be a positive experience, because it’s much easier to be cynical now about collective living and the hippie dream gone wrong.

CF Though in Europe there are still a number of collectives that are basically squats, as in Germany and Holland, and don’t you still have squats in London?

BR It’s harder now because the laws have changed; the squats don’t last as long.

I think in Amsterdam there are some, but we wanted the collective to be rural. We were very happy with the way it turned out, because everybody got along really well and it was an amazing experience for us as well. We would set up the environment and the people, and then film what would happen in that situation.

CF It’s sort of a Jean Rouch approach.

BR Yeah, Rouch was totally a model for that part of the film, as was Milestones (1975) by Robert Kramer and John Douglas.

The second part of A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness is more simple and quiet, you see Robert living in solitude in the north of Finland. But there is a sense of unease in his solitude; he doesn’t seem totally comfortable there. So again it’s a confrontation with the sublime, the landscape. It’s alluring but, in the true sense of the sublime, it’s also frightening. The north of Finland has this incredibly ominous atmosphere about it. It’s very beautiful, but at the same time something’s not quite right. In the last part of the film, Robert’s playing in a black metal band and that’s one of the reasons why we chose him; he’s got good presence, he looks great, and he’s a performer. Ben had showed me a YouTube clip of him performing and I felt he was right for the film. When he performs he gets into a trance-like zone and that was important.

CF Is the black-metal band his or did you find a band for him to play with?

BR They’re all accomplished musicians who play in different kinds of bands; only two of them play in black-metal bands.

CF Oh, so you created a band.

BR Yeah, they were all brought together as a fictional band, but close to what they do.

CF What’s Robert A.A. Lowe’s real life music like; is it black metal?

BR No, his own music is solo and it’s more drone-like, and he uses vocal and electronic loops; it’s totally different than black metal.

CF I looked at the trailer; it’s beautifully shot. What format did you and Ben Russell shoot on?

BR Super 16. We basically shared everything from the ideas, the shooting and editing, as well as cooking and carrying everything. (laughter)

CF I saw one of Russell’s films in the 2009 Toronto Film Festival. The one in Suriname with the two brothers, Let Each One Go Where He May (2009). So how did you collaborate on the editing for A Spell To Ward Off the Darkness?

BR Ben has been living in Paris so I would just go over there. He’s usually at the editing controls because he’s faster with Final Cut Pro. Basically I’d sit beside him or walk beside him—he prefers to sit down and I like to walk around and drink lots of tea. We just did it all together. For me it was the first time I had collaborated like that. I’ve worked with people before; I’ve made a couple of films with my friend Paul Harnden who’s a clothes designer, but that was a slightly different dynamic as he’s not a filmmaker by trade. With Ben and I there’s a potential for disaster because we’re two filmmakers who are totally clear about what we do. But the collaboration was really smooth, and I think the reason for that was that we both wanted to push each other to do something we wouldn’t normally do, so the end result is not something we would have made by ourselves.

CF I would say the similarity is in your mutual interest in filming less-traveled, far away places, and working with indigenous people.

BR Formally our films are quite different. But both of us have a desire to make cinema that is not a representation of the world, but that comes from actual people and places—and is then transformed through cinema into something that isn’t the world, it’s new.