Downtown, Before the Gentry Moved In

By MARTHA SCHWENDENER

Published: December 25, 2012

For some of us it’s still a bit of a shock to encounter a Whole Foods on the corner of Bowery and Houston Street with a sign outside that reads, “Bowery Self-Serve Cookie Bar: Because It’s Been That Kind of Day.” For more than a century, after all, and until very recently, the Bowery was known for trafficking in substances considerably stronger than cookies.

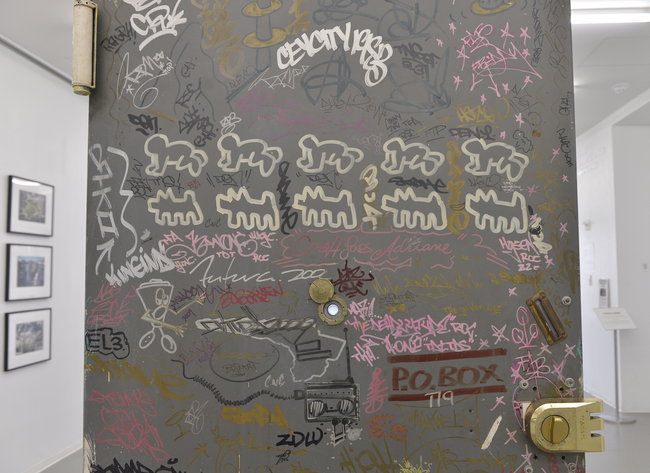

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

“Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969-1989”: The door to an apartment is among the displays in this exhibition on the fifth floor of the New Museum.

The New Museum, two blocks south, offers the same kind of cognitive dissonance: a gleaming tower devoted to high-end globalized art, it is a similar product of gentrification. And yet, as a museum, it has the ability — some would say the mandate — to address its relationship to the past and its location. This is exactly what “Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969-1989,” organized by Ethan Swan, an education associate at the museum, does — and rather successfully for a small show.

The definition of art here is appropriately broad. A tattered Ramones T-shirt sits on a hanger across from the door taken from Keith Haring’s Broome Street apartment, blazoned with tags by graffiti artists like Fab 5 Freddy. (Interestingly, curators were made aware of the door by a museum security guard who lives in the area.)

Fliers that were originally (and illegally) wheatpasted downtown now cover the walls of a back hallway on the museum’s fifth floor, where the show is mounted, announcing long-ago performances by bands like the Contortions, Liquid Liquid, Y Pants, Glenn Branca and the Ramones. (“New York’s Phenomenal Pop Combo,” says a flier for a show at CBGB, a Bowery alt-culture landmark.) Others advertise art exhibitions, like a flier for Artists for Survival at ABC No Rio, which reads, “You Want It? We Got It. 1. Gurgling Sculpture/2. Metal Clothing/3. Paintings/4. Cast Heads/5. Posters/6. Objects de Religion/7. Outdoor Sculpture Garden/8. And More.”

A similar sort of humor pervades Marc H. Miller and Bettie Ringma’s “Paparazzi Self-Portraits” (1976-80), a series of faded snapshots displayed in a vitrine for which the artists took turns photographing each other with celebrities like Andy Warhol, William S. Burroughs and Angela Davis. Later the concept of celebrity took a slightly different turn, as Mr. Miller and Ms. Ringma spent more time at CBGB photographing musicians like Patti Smith, the Talking Heads, Suicide and the Ramones.

Experimental film and video are represented by Coleen Fitzgibbon’s “Daily News” and “L.E.S.” (both 1976), which use appropriated images and sound to create a picture of ’70s downtown life; Paul Tschinkel’s “Hannah’s Haircut” (1975), a black-and-white video depicting the artist Hannah Wilke, topless, giving Claes Oldenburg a haircut; and films of Charles Simonds creating his miniature, archeology-inspired “Dwellings” in different public spaces.

A series of three thin, zine-like publications titled “Bowery Artist Tribute” (Volumes 1-3) extends the show’s reach into oral history and documentation. By the beginning of its run in September, more than 400 artists had been cataloged, with information about their creative output, from minimalist sculpture to graffiti.

As marginal as many of these artists were during the era covered by this show, there are plenty of clear links between what’s on view here and “official” art and the art world. Mr. Simonds, for instance, eventually created one of the “Dwellings” in a stairwell at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Fragments from drip-style paintings that Mr. Haring made and displayed in public places connect his activities with those of earlier downtown painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Martin Wong’s canvas “Study for La Vida” (1984) is in the lineage of ’30s Social Realism. Adrian Piper’s “Hypothesis: Situation #11” (1969) is a classic photo-conceptual work, complete with grid paper and text. And Marcia Resnick and Cindy Rupp’s photographs mounted in outdoor sites in the ’70s hew to the conventions of site-specific installation, which became popular right around that time.

Such connections can be stretched by revisionism, as in a wall label describing Adam Purple’s Garden of Eden — a guerrilla garden cultivated on empty, city-owned lots east of the Bowery — as a “monumental earthwork.”

Adam Purple’s giant, circular yin-yang garden was bulldozed in 1986 to make way for a housing project, and photographs of it in the show are something like pagan relics unearthed at a long-since Christianized religious site. Which may be an apt metaphor for the Bowery and its environs as a whole, a place where pagan culture once ruled, but now, rather than being entirely erased, is visible in traces, having been absorbed and transformed by the new era and ethos.

“Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969-1989” continues through Dec. 30 at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, at Prince Street, Lower East Side; (212) 219-1222, newmuseum.org.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: December 27, 2012

Schedule information on Wednesday with an art review of “Come Closer: Art Around the Bowery, 1969-1989,” at the New Museum in Manhattan, included an outdated closing date for the exhibition. It runs through Sunday, not through Jan. 6.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/26/arts/design/come-closer-at-the-new-museum.html?_r=2&